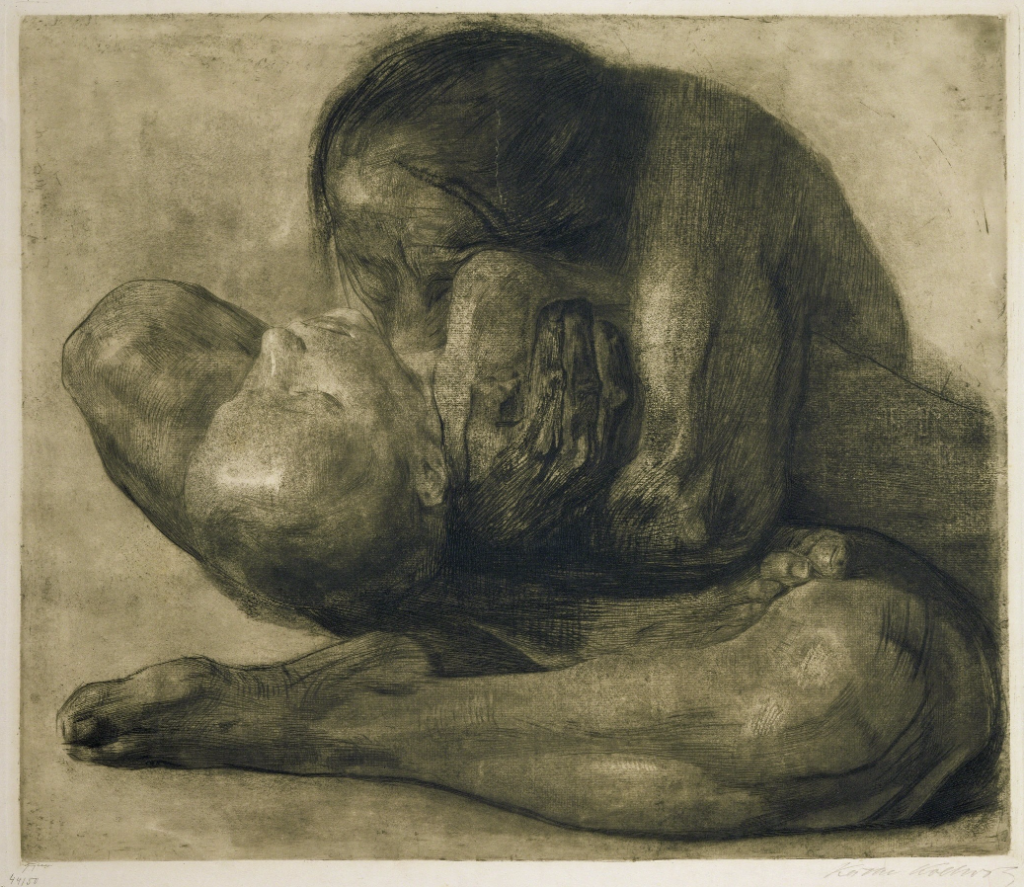

Art against war

In 1927, the French playwright Romain Rolland wrote about the tragic and powerful images of Käthe Kollwitz: “It is the greatest poem of today’s Germany,” a poem that reflects the trials and sufferings of the humble and the simple.

This woman with a virile heart gathered them into her eyes and her maternal arms.She is the voice of the silence of the sacrificed peoples.

A universal voice, able to translate the tragedies of early 20th-century conflicts into a collective and absolute cry.

A voice that, even today, in the face of the massacres in Gaza, holds an inexhaustible value—a deep sense of the present and of relevance that only art can cultivate and convey.

However, the unjust and heart-wrenching scenes of Käthe Kollwitz do not belong to today, but were born in the dark heart of the short twentieth century—just like those of all who have denounced war, furiously waving the white shroud of our shared humanity.

The red wedges of Lissitzky, the torn bodies in the trenches of Otto Dix, Picasso and Guernica, the opalescent concentration camps of Carlo Levi, Guttuso’s crucifixions, the thorned gate of the Fosse Ardeatine by Mirko Basaldella, the uprisings of Emilio Vedova raised with brushstrokes and pitch. Icons seared into our eyes and our consciences—born of militant thought and forged under dictatorships, against all forms of established power, as weapons of accusation and resistance.

“Necessary” art, as Mario De Micheli once said, urging artists to speak and act more, so that ignorance of violence would not prevail over the values of life. That is why today, as Europe remains silent (and, alas, at times even laughs…) in the face of genocide, invasion, and death, culture is called upon to become politics—to transmit civil values against the backdrop of a historical context that has plunged into criminality.

Just a few days ago, on La Stampa (May 26), a powerful and moving editorial by Manuela Gandini titled ‘A Call Against Weapons Is Needed’ tried to shake our consciences in the face of ongoing mass extermination.

It recalled moments in the past when intellectuals rose up en masse against injustice and abuse, citing examples from Vietnam to the Balkans—like Marina Abramović, who at the 1997 Venice Biennale spent days brushing a heap of cow bones, stripping them of rotting flesh.

So let us hang white sheets from our windows once more, but let us also ask art to become an active witness again—to scream through images, to strike at the raw nerves of our compassion, to cling desperately to the community, and to call for participation to overcome horror, armed only with what Milan Kundera called the precious ‘union of culture and life, creation and people.